When we identify where our privilege intersects with somebody else’s oppression, we’ll find our opportunities to make real change.

Ijeoma Oluo

Here we provide brief overviews and definitions of key terms and concepts related to YCD programs and the wider movement for social justice. We also encourage youth and adult mentors to engage in meaningful, facilitated conversations on each of these concepts. During these discussions, reflect on how these ideas connect to your own experiences, how they show up in others’ stories, and how this language can empower positive social change.

Identity

Identity is a word that we hear and use often, yet has profound meaning that can sometimes be overlooked. How would you define your identity to someone you are meeting for the first time? It’s helpful to actually try this now, to see what comes to mind and to reflect on it.

We all have ways we think of and view ourselves, whether it be our likes and dislikes, hobbies and the way we spend our time, our goals and aspirations, or experiences we’ve had in the past. These are all important aspects to identity, and add up to how we view ourselves as unique individuals. We can call this our individual identity.

In addition to our individuality, though, each of us also experience the world as members of social categories. Examples include being Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Hispanic, Indigenous, deaf, autistic, American, Canadian, gay, etc. Being a member of these categories contributes another important part to our identity, or what we can call our social identity.

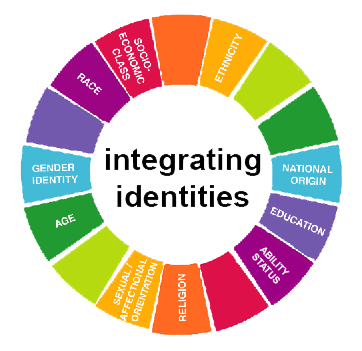

Each of us belong to many social categories, which overlap, mix, and affect us in different ways. Below is a circle that shows several of the categories that each person could fill in with their specifics (i.e. age = teenager).

Which categories do you belong to? Which ones did you list immediately when you started reading this section, and which did you not think of until seeing this graphic? It’s interesting and noteworthy to reflect on which social categories matter a lot to our identity, and which go unnoticed. Think about this in your own context, and we’ll bring it back up later.

Diversity and Inclusion

While the words diversity and inclusion are closely related, and often used alongside one another, they have distinct meanings. It’s important to use each word when it’s appropriate, and not use them interchangeably.

Diversity, in its simplest form, means differences or variety within a group. This word is about who’s in the group.

Inclusion, on the other hand, means every person is participating in a group, and power is shared among the members of the group. This word is about how the group members interact.

You can have diversity without inclusion (i.e. a wide variety of students, but the group is dominated by students from specific social categories) and you can also have inclusion without diversity (i.e. a highly inclusive group, but the group members are all from similar backgrounds and identities).

The word diversity has been used (incorrectly) by some to refer to people who don’t hold power or aren’t the dominant group in society. This most often happens when talking about race; people of color are referred to as “diverse people” because they are not white, and diversity programs or clubs are thought to only relate to students of color, or to LGBTQ+ students. Using the word diversity this way is really about “othering” people who are not in a dominant social category, and should always be avoided.

Within the context of a school group or club, take care to craft recruiting efforts that create a diverse group, as well as to craft norms and ways of meeting that result in an inclusive environment. Both diversity and inclusion are important. Note these efforts will require asking who’s not represented or included, and then taking extra effort to get those voices involved in your group or club. YCD’s Guide has suggestions and tips to help student groups with creating highly diverse and inclusive memberships.

Privilege

Historically the word privilege has conveyed a good thing, i.e. I have the privilege to introduce so-and-so … In this respect, the word meant pleasure or opportunity. You may still hear the word used this way from time to time.

More recently, the word privilege has been reframed by scholar and feminist Peggy McIntosh to mean the unearned benefits each person receives for belonging to certain social categories.

One example of privilege that many people don’t think of is being right-handed. Most of the human population is right-handed, but there is a large number of people who use their left hand for most activities. Left-handed sports equipment (baseball mitts, golf clubs, hockey sticks, etc.) is not always available. Sometimes desks in classrooms are designed with right-handedness in mind, so that a left-handed person could not use the desk. In both these cases, the right-handed people did not do anything to earn proper-fitting sports equipment or desks shaped in a way that works for them; they were in a dominant social category (right-handed people), and the people designing these tools assumed righthandedness as a standard when making them.

The above examples may seem relatively harmless, but when it comes to other aspects of privilege, the results can be very serious or even deadly. Here’s a list of examples of privilege relating to race specifically that can illuminate the many ways privilege exists, but often goes unnoticed by those who benefit from it.

Examples of privilege exist across every social category — race, gender, sexuality, disability, religion, ability, socioeconomics, and much more.

We study and talk about privilege in order to identify spaces where society has deemed certain social identities as preferred. People who have privilege in those spaces have an obligation to promote and include the voices of people who have less privilege, and to work toward a more equitable society that values everyone’s identities.

To go deeper on the topic of privilege, read Peggy McIntosh’s essay White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. For a demonstration of white privilege (privilege based on race and skin color), watch this TikTok video that went viral:

Allison Holker Boss on TikTok

blacklivesmatter @twitchtok7 | White privilege Is real | Allison Holker Boss (@allisonholkerboss) has created a short video on TikTok with music Check Your Privilege by Big Mamma.

Marginalization and Oppression

What causes some social identities to be privileged by society, and others to not be?

The answer is simple: power.

Social groups or identities that hold power will create ways of living that benefit their category. This may take the form of laws, policies, social norms, or ways of living that explicitly (directly) benefit the dominant group, or may be more subtle but have the same effect. This is a widely documented behavior in sociology.

Marginalization refers to the treatment of people who are not in the dominant group, who are treated as secondary, inferior, or unimportant compared to those who are in the dominant group.

Oppression is the systematic (repeated and persistent) marginalization of a specific group over time to deny that group access to power.

Marginalization can happen in small and large ways, over time or suddenly. There are numerous examples of marginalization, but we’ll use voting rights as a specific area to focus on, as voting is so fundamental to democracy and the control of political power in the U.S.:

- Black people were not given citizenship during the founding era of the U.S. — even those who were not enslaved. Only three states granted free Black people the right to vote before the Civil War.

- After the Civil War, the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution extended voting rights to the formerly enslaved in 1870, though this was still for men only.

- “Jim Crow laws” were enacted on the state and local level across the South in the late 1800s and early 1900s to prevent Black people from exercising their right to vote.

- Even when women were allowed to vote in 1920, it really meant white women were allowed to vote because of the Jim Crow laws.

- It wasn’t until the 1960s when Black people demanded access to voting through the Civil Rights Movement that Jim Crow laws were ruled unconstitutional by the courts, or were repealed by legislative action.

- The Civil Rights Movement did not stop all attempts to limit the Black vote; voter suppression efforts continue today. As one example, because of racist policies more recently, 1 in 13 Black Americans have lost their right to vote today due to felony convictions.

The above examples on voting may be isolated examples of marginalization, but taken together, they add up to a history of oppression of Black people to deny them access to political power in the U.S.

Oppression exists across every social category, with different names (racism, sexism, ableism, etc.) but similar features. Below is a useful table to point out the different major types of oppression that exist across major social categories, and how each relates to privileged and targeted social groups (click on the image to download a copy). Note some of these categories and privileges change in certain contexts; the matrix below is specific to the United States’ history and culture.

Intersectionality

Building on the prior concepts of identity and privilege, intersectionality aims to illuminate and expose how people who hold multiple marginalized identities experience oppression and marginalization in different and more profound ways.

For illustrative purposes only, think of three hypothetical people: a Black woman who is a single mother; her brother, who is gay; and her father, who is a veteran and uses a wheelchair due to injury. All three people are Black and experience anti-Black racism as they go through society. At the same time, the father experiences ableism as well as racism, while the woman experiences sexism as well as racism, and the brother experiences racism mixed with homophobia. Each of these experiences is distinct and unique from the other. In this respect, intersectionality reminds us of the complexity of each person, that each individual holds multiple identities, and warns us to avoid generalizing about how marginalized people experience oppression.

Going further, people holding multiple marginalized identities also experience oppression in deeper and more profound ways. For some specific examples and to learn from the expert, watch this TED talk from Kimberlé Crenshaw, who identified the concept:

Bystanders, Allies and Accomplices

When a group in power acts based on prejudice, that creates oppression. History is filled with examples of oppression in a wide variety of forms, ranging from the extreme — the Nazis in Germany, or apartheid in South Africa, or the genocide of Indigenous people throughout the founding and early days of the U.S. — to modern-day examples that may not come to mind at first, but are still oppressive — for example, mass incarceration of Black and Latinx Americans, or efforts to restrict voting rights.

Critical in understanding oppression is the role of bystanders in enabling these actions. Whether in Nazi Germany or in the modern-day U.S., those in power can only oppress marginalized people when bystanders allow it to happen. We like to think when we see something wrong happen, we won’t be a bystander — but the truth is much more complicated. To explore this idea, watch the video below and consider examples or incidents from your own life.

The video above featured someone who just needed help, not someone facing oppression or staring down those with power. When the stakes are high and there is personal cost to standing up, the likelihood of all of us being bystanders rises, so it takes all the more effort to stand true to our values and not be bystanders.

In these scenarios, we need to focus on shifting from being bystanders to become allies and accomplices to those facing oppression and discrimination. These two words have different meanings, and the distinction is important.

An ally is someone who doesn’t share the same identity or oppression as the person being oppressed, but stands with them, whether literally or figuratively. An ally is a friend, a helper, a support. There are always times in our lives when we need allies to support us, and building relationships with people from different identities can help you become a better ally. Most important in these cases is to let the person facing the oppression or discrimination tell you how they want you to show up and support them.

An accomplice, however, takes this situation and tries to fix the underlying problem. An accomplice doesn’t simply nurture or help a person facing oppression or discrimination — they work to dismantle the source of power that is causing the oppression. This is where activism lives and breathes. In many cases you may have helped one person facing oppression as an ally, but there are hundreds, thousands or millions more facing the same oppression. An accomplice works with those facing the oppression to get at the root and end it, rather than helping just one individual in need.

Throughout everyone’s lives, there will always be scenarios where it’s important to be an ally, and other times when you’re given opportunities to be an accomplice. Not every situation requires every person to take the same role. Most important in all cases is moving ourselves out of a place of being a bystander, into being an ally or accomplice, and letting those facing oppression lead the fight to end that oppression.

Social Justice

Social justice can be a loaded term for some people, but we believe it’s central to the work of advancing inclusion and fighting oppression.

As outlined in the definition to the the right, social justice is a vision of a future without oppression — not just without racism, or sexism, or homophobia, or ableism, but without all forms of oppression.

In a socially just world, every person is free from stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination, and oppression. Some folx use the word liberation to describe this “promised land” or vision for the future.

Some would say such a vision is impossible to achieve, and are skeptical it’s realistic to talk in terms of liberation or social justice. However, such thinking is defeatist and benefits those in power now. We firmly believe positive social change is not just possible, but necessary. Those who are oppressed don’t have the option of giving up, because their lives and livelihoods depend on it.

This is the urgency of making positive social change. Will you join the student movement to make it that much closer to reality?

And I say that if we will stand and work together, we will bring into being that day when justice will roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream. We will bring into being that day when America will no longer be two nations, but when it will be one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

Martin Luther King, Jr.